What Are Rare Earths?

Rare earths, also known as rare earth metals, consist of 17 elements: 15 lanthanides—Lanthanum (La), Cerium (Ce), Praseodymium (Pr), Neodymium (Nd), Promethium (Pm), Samarium (Sm), Europium (Eu), Gadolinium (Gd), Terbium (Tb), Dysprosium (Dy), Holmium (Ho), Erbium (Er), Thulium (Tm), Ytterbium (Yb), Lutetium (Lu)—plus Scandium (Sc) and Yttrium (Y).

They are typically silvery-white, soft, and malleable metals. Most are paramagnetic under normal conditions, meaning they are weakly attracted to magnetic fields and lose their magnetism when the field is removed. Only a few display ferromagnetic properties, such as Gadolinium (below 20°C), Dysprosium (below ~85K), and Holmium (below ~20K).

Chemically, rare earth metals are very reactive—second only to alkali and alkaline earth metals—placing them among the more active metallic elements.

💡 Ferromagnetism means a material can retain magnetism after an external magnetic field is removed (like permanent magnets), while paramagnetism means the material is only magnetized in the presence of a magnetic field and loses it when the field disappears.

Based on atomic weight and periodic placement, rare earths are generally categorized into two groups: light rare earth elements (LREEs) and heavy rare earth elements (HREEs). Sometimes a middle category is also included.

| Category | Light Rare Earths (LREE) | Heavy Rare Earths (HREE) |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | More abundant in the Earth’s crust; easier to mine; lower environmental impact. | Less abundant; harder to extract; more environmental concerns; used extensively in high-tech applications. |

| Elements | La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Sm, Eu, Gd | Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu, Sc, Y |

| Applications | Fluorescent materials, chemical catalysts, magnet production, glass manufacturing | High-performance magnets, lasers and optics, military navigation, nuclear energy, superconductors, precision instruments |

Despite their name, rare earths are not actually rare in terms of natural abundance (except Promethium, which is radioactive and extremely scarce). For instance, Cerium ranks 25th in Earth's crustal abundance—comparable to copper. What makes them “rare” is not scarcity but the difficulty and cost of extracting and refining them. These elements tend to occur together and are often found with radioactive elements, making separation costly and environmentally intensive.

Overview of the Rare Earth Industry

Market Size

According to Grand View Research (2024), the global rare earth market was valued at USD 3.95 billion in 2024, with a projected CAGR of 8.6% from 2025 to 2030—reaching around USD 4.29 billion in 2025. However, this figure only represents upstream and midstream activities (mining, separation, refining, and oxides/metals), which make up just ~0.002% of global economic activity. Despite its small scale, the rare earth sector is a critical strategic industry due to its essential downstream applications.

Note: These figures exclude downstream manufacturing (e.g., magnets, EV motors, wind turbines, and defense equipment), so the total value of the rare earth supply chain is significantly higher.

Supply Outlook

Primary supply of rare earths is projected to grow from 57,000 tons in 2021 to 107,000 tons by 2040. Even with increased recycling (from 22,000 to 43,000 tons), demand is expected to outstrip supply.

According to the IEA:

- Under the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), supply will reach ~100,000 tons by 2040.

- Under the Accelerated Policy Scenario (APS), demand could exceed 125,000 tons.

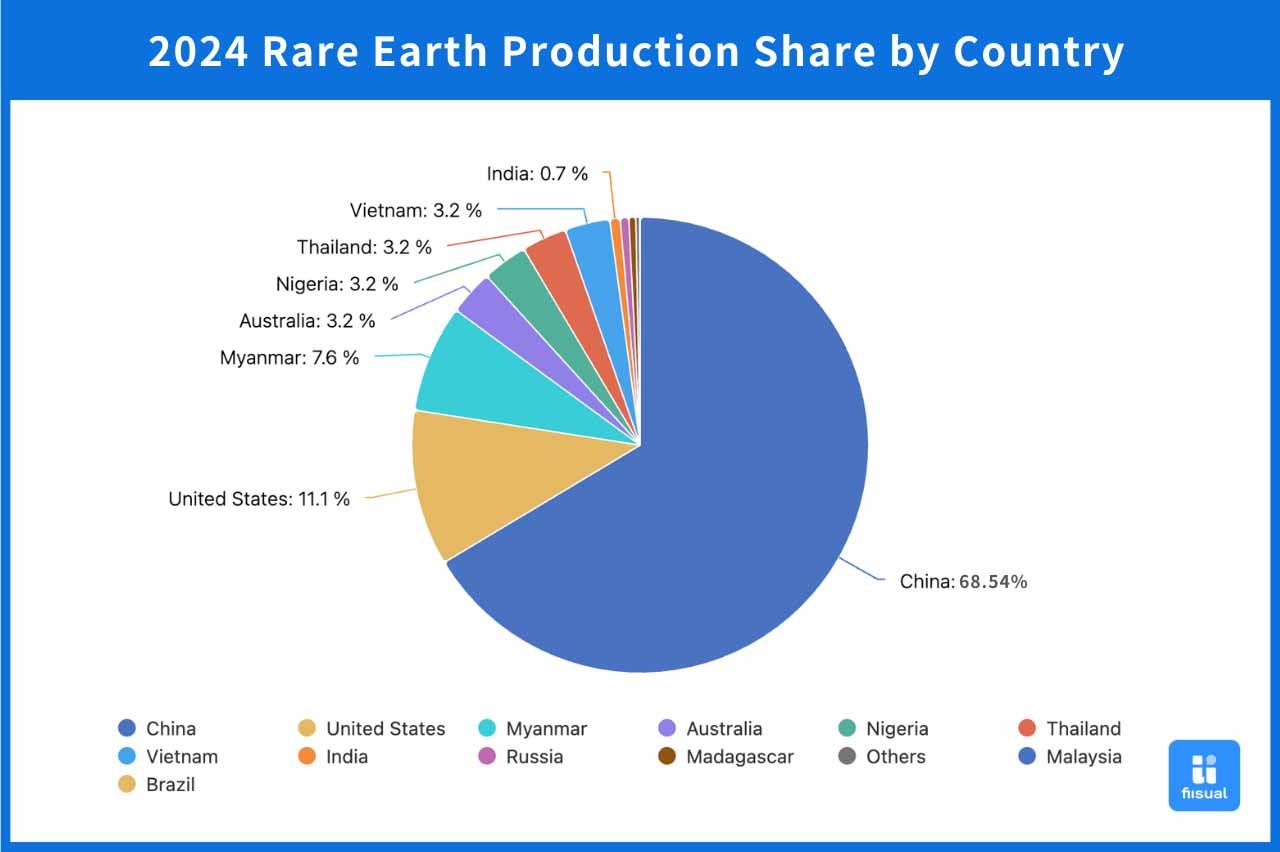

Global Reserves and Production (2024)

| Country | Rare Earth Reserves (Share) (%) |

|---|---|

| China | 48.41 |

| Brazil | 23.11 |

| India | 7.59 |

| Australia | 6.27 |

| Russia | 4.18 |

| Vietnam | 3.85 |

| United States | 2.09 |

| Greenland | 1.65 |

| Tanzania | 0.98 |

| South Africa | 0.95 |

| Canada | 0.91 |

| Thailand | <0.01 |

| Others | 0.28 |

| Country | Rare Earth Production Share (2024) (%) |

|---|---|

| China | 68.54 |

| United States | 11.42 |

| Myanmar | 7.87 |

| Australia | 3.30 |

| Nigeria | 3.30 |

| Thailand | 3.30 |

| Vietnam | 3.30 |

| India | 0.74 |

| Russia | 0.63 |

| Madagascar | 0.51 |

| Others | 0.28 |

| Malaysia | 0.03 |

| Brazil | 0.01 |

China remains the world’s largest producer with a 68.5% production share, despite holding only ~48% of global reserves. Southeast Asia (Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia) collectively contributes ~14.5%, forming a rising rare earth production cluster.

Demand Outlook

Global demand for rare earths is expected to nearly double between 2021 and 2040—from ~78,000 to 150,000 tons, driven heavily by clean technologies.

- Clean tech (e.g., EVs, wind turbines) demand is forecast to grow from 11,000 to 47,000 tons—a fourfold increase, making it the key growth driver.

- Other uses (e.g., electronics, defense, machinery) are projected to rise more modestly—from 67,000 to 103,000 tons.

This reflects the growing importance of rare earth magnets in global energy transition and electrification efforts.

Summary: Strong Demand, Fragile Supply

Rare earths are often referred to as the "vitamins of industry"—critical in small amounts but essential for modern technologies. However, their supply chain is vulnerable due to geographic concentration and production complexity, creating a strategic imbalance.

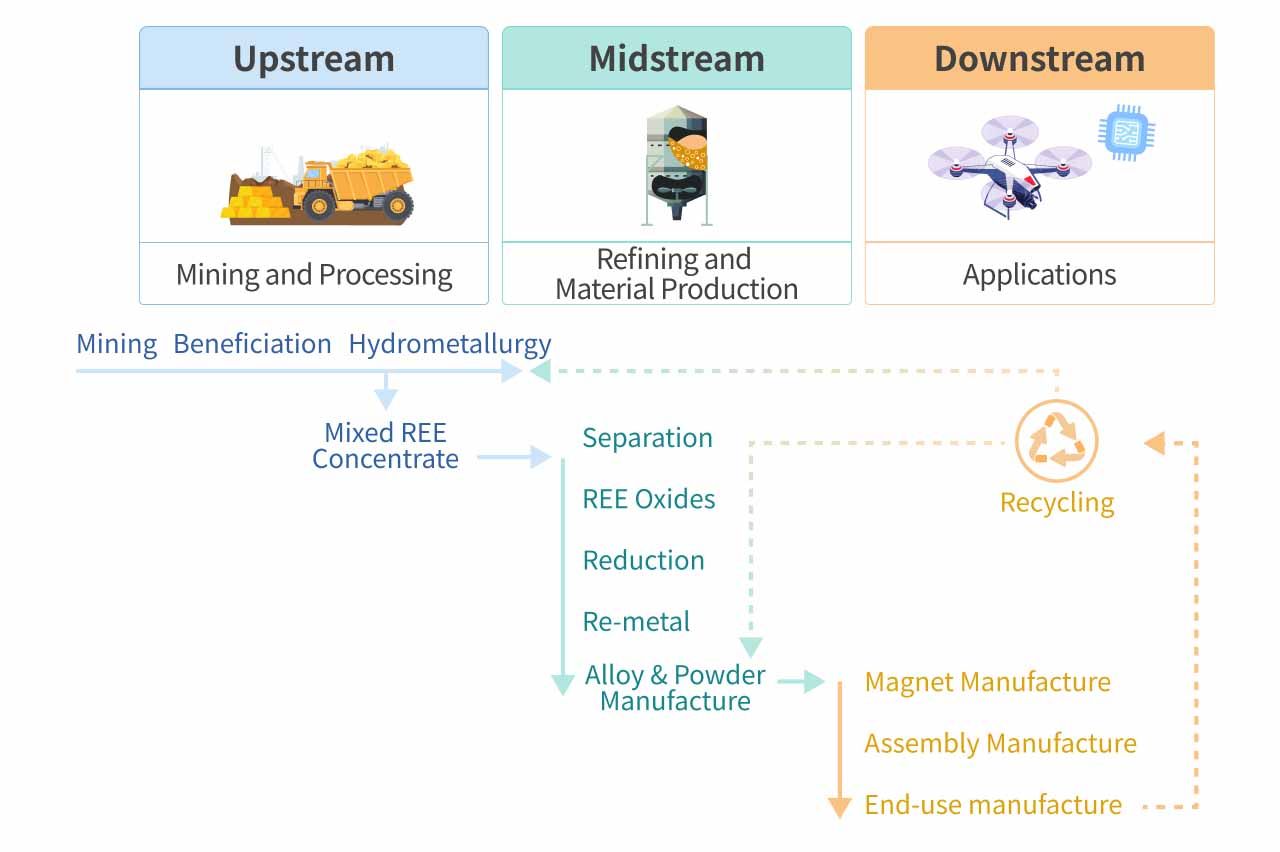

Rare Earth Supply Chain Overview

The rare earth supply chain has three main stages—upstream mining and processing, midstream refining and material production, and downstream application manufacturing—plus recycling as a supplementary source.

| Stage | Process | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Upstream | Mining | Extracting rare earth-bearing ore. |

| Beneficiation | Crushing and concentrating ores into high-grade rare earth concentrate. | |

| Hydrometallurgy | Using solvents to extract rare earths into solution form. | |

| Mixed REE Concentrate | Combined output of multiple rare earths for midstream separation. | |

| Midstream | Separation | Solvent extraction or ion exchange to separate individual REEs. |

| REE Oxides | Isolated oxides (e.g., Nd₂O₃, Pr₆O₁₁) used in magnet/metals production. | |

| Reduction | Reducing oxides into metallic form (electrolysis or metallothermic methods). | |

| Rare Earth Metals (Nd, Pr, Sm, Dy & Tb) | High-purity metals (e.g., Nd, Pr, Dy, Tb). | |

| Alloy & Powder Manufacturing | Creating magnet-grade alloys and metal powders. | |

| Downstream | Magnet Manufacturing | Producing NdFeB and other high-performance permanent magnets. |

| Module Assembly | Assembling magnets into motors, sensors, speakers, etc. | |

| End-Use Manufacturing | Final product manufacturing (e.g., EVs, turbines, electronics). | |

| Extended | Recycling | Extracting rare earths from end-of-life products for reuse. |

Value Concentration in the Midstream

The most value-added stages are in the midstream—especially separation and alloying, over 90% of which are concentrated in China. Rare earth prices rise significantly as materials move through the value chain.

| Stage | Product | Avg. Price (USD/MT, as of Oct 17) | Value Multiplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrate | Monazite | $6,012.52 | - |

| Oxide | Neodymium Oxide | $70,352.65 | x 11.7 |

| Metal | Neodymium | $88,018.29 | x 14.6 |

| Magnet | NdFeB (N52 SH) | $42,520 | x 7.1 |

| Recycled | Nd/Pr from Scrap | $66,320 | x 11 |

Although permanent magnets dominate rare earth use, they are alloys (not pure RE metals), and thus priced lower than refined metals. China’s dominance in midstream processes secures its control over the industry’s most profitable segment.

Overall, China has secured the majority of profits in the global rare earth industry by dominating the most value-added segment of the supply chain—the midstream processing stages, such as separation and alloying. In addition, its massive production capacity for permanent magnets and the scale of its domestic application market have further reinforced its leadership position in the global rare earth supply chain.

Strategic Importance of Rare Earths

Strategic Leverage and Export Controls

China controls both the world’s largest reserves and production capacity of rare earths—especially in midstream refining and alloying, giving it unmatched power over the global supply chain.

China has historically used this position as leverage in trade and diplomacy, such as the 2010 export suspension to Japan. In 2025, China implemented two rounds of rare earth export controls—in April and October.

October 2025 Controls (Effective Dec 1)

- Tightest restrictions ever announced by China’s Ministry of Commerce.

- Expanded list: Added 5 more RE metals (Ho, Er, Tm, Eu, Yb) to the 7 previously restricted (Sm, Gd, Tb, Dy, Lu, Sc, Y)—total 12 REEs now subject to approval.

- Stricter usage restrictions: Any product or process involving advanced chips (≤14nm), 3D NAND (≥256 layers), military AI, etc., requires case-by-case licensing.

- Content thresholds: Export of any product containing >0.1% Chinese rare earths must be licensed.

- Equipment and technology now restricted: Including refining and alloying tools and know-how.

- Military-related exports banned outright.

Strategic Intent

These restrictions go beyond economic concerns—serving geopolitical and negotiation purposes. China is signaling its readiness to leverage rare earths in ongoing trade talks with the U.S., particularly in semiconductors and AI.

Rare earth supply control and semiconductor fabrication dominance are becoming the two key battlegrounds in the U.S.-China tech rivalry.

Temporary Delay Post-Summit

After the Oct 30 summit between President Xi Jinping and President Trump, China agreed to delay the new controls for one year. While this eases short-term pressure, it has triggered stockpiling behavior and heightened urgency in Western efforts to diversify supply.

Long term, China’s use of rare earths as a geopolitical bargaining chip is forcing supply chain reshuffling across the globe.

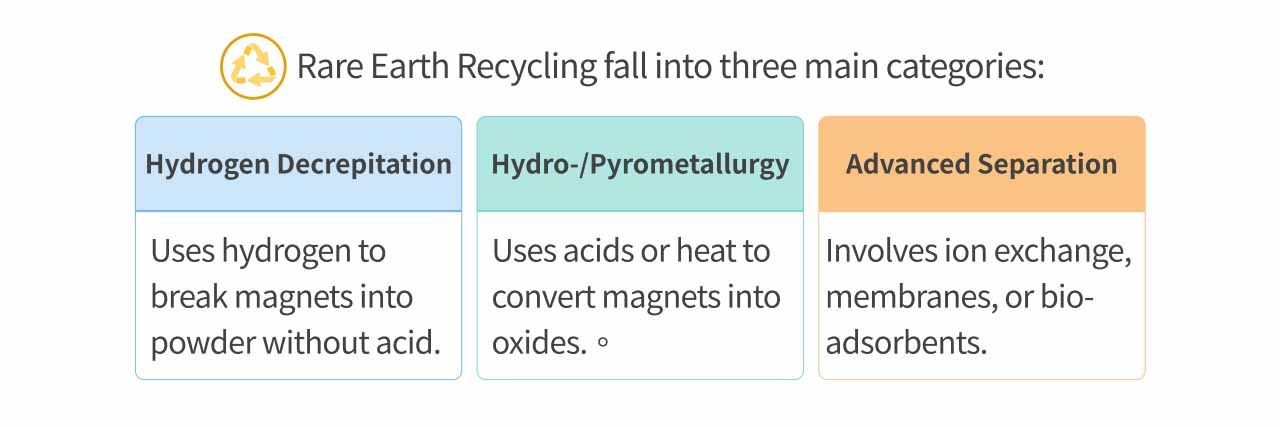

Building Alternatives Through Recycling

To reduce dependence on China, rare earth recycling is becoming a strategic priority. Technologies fall into three main categories:

Hydrogen Decrepitation (Magnet-to-Magnet)

- Uses hydrogen to break magnets into powder without acid.

- Retains original alloy structure; reduces energy use by 90%.

- Key players: HyProMag (UK/US), Noveon (US), Hitachi Metals (Japan).

Hydro-/Pyrometallurgy (Chemical Extraction)

- Uses acids or heat to convert magnets into oxides.

- Firms like Phoenix Tailings (US) and Cyclic Materials (Canada) use non-toxic or staged extraction.

- Solvay and Umicore (EU) recycle polishing powders and catalyst waste.

Advanced Separation

- Involves ion exchange, membranes, or bio-adsorbents.

- Players include ReElement (US), REEcycle (US), Oak Ridge and Ames Labs (US).

Apple-MP Materials Case Study: Apple signed a $500M deal with MP Materials to secure U.S.-made NdFeB magnets and is building recycling lines at Mountain Pass. A Texas facility using recycled feedstock will launch in 2027.

Summary: Rare Earth Recycling Shows Promise, but Limitations Remain

Currently, global rare earth recycling accounts for less than 1%, mainly due to the high difficulty of recovering materials from consumer electronics. However, many countries have begun exploring the recovery of rare earths from industrial by-products to expand secondary resource channels.

Compared to reopening mines and building new facilities—which could take over a decade to establish a full supply chain—enhancing existing recycling technologies appears to be the more viable short-term solution. Despite growing investment in recent years, rare earth recycling remains constrained by several key challenges:

- High costs – Recycling is generally more expensive than mining raw ore.

- Complex material composition – Waste sources are chemically diverse and hard to process.

- China’s dominance – China still controls the critical refining and separation stages.

Additionally, setting up new separation and smelting facilities requires long-term capital and time. Many waste streams also contain coatings, mixed materials, and other contaminants, making dismantling and purification technically demanding.

Global Strategic Alliances

The global rare earth contest is now split into two camps:

- China-led supply camp

- Western demand camp (U.S.-centered)

U.S. International Partnerships

| Partner | Date | Key Points |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Oct 20, 2025 | Joint mining, refining, and recycling; $3B co-investment; EXIM financing; Lynas-Noveon magnet partnership. |

| Malaysia | Oct 26 | No export restrictions to U.S.; accelerated project licensing; still bans raw ore exports. |

| Thailand | Oct 26 | Co-develop refining industry; export bans on raw ore; priority tech transfer rights. |

| Japan | Oct 27 | Bilateral funding for mining/separation; tech R&D; joint mapping and security plans. |

| South Korea | Oct 29 | POSCO and ReElement to build U.S. base for rare earth separation and magnet production. |

Australia and Japan are U.S.’s most advanced partners, with both upstream and midstream capabilities. China alternatives such asSoutheast Asia are earlier-stage partners focused on regulatory alignment and basic processing capacity.

U.S. Corporate Investment Projects

| Project Name | Industry Role | Investment Amount / Scale | Key Partnerships | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP Materials | The only U.S.-based company with large-scale rare earth mining and processing capabilities; focuses on NdPr (neodymium, praseodymium) magnet material supply chain. | Direct funding from the U.S. government; purchased $400 million in preferred shares as part of a multi-billion dollar support package. JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs provided $1 billion in loans. | 1. Signed agreement with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) to build a full domestic rare earth supply chain (from mining to magnet manufacturing). 2. Floor price set at $110/kg for NdPr with a 10-year guaranteed procurement contract. 3. DoD acquired a 15% equity stake, replacing Shenghe Resources as largest shareholder. 4. Building the "10X Facility" magnet plant (slated for 2028, 10,000 tons/year capacity). | Previously focused on mining and separation, now expanding across the entire value chain from mining to downstream magnet production and recycling. |

| Vulcan Element | Rare earth magnet manufacturer. | Total investment: $1.4 billion. U.S. government loan of $620 million, $50 million in federal grants, $550 million in private investment. ReElement expansion also received $80 million in government loans. | 1. Working with U.S. government and ReElement Technologies to create a 100% domestic rare earth magnet supply chain. 2. Constructing a 10,000 tons/year magnet factory and expanding capabilities for recycling and e-waste recovery. 3. U.S. government holds equity in Vulcan Elements to secure supply chain resilience. | Focused on rare earth magnet manufacturing. |

| Ucore Rare Metals | Midstream processing (refining/separation). | U.S. Department of Defense provided $22.4 million in grants to support commercialization of RapidSX. Louisiana state provided $15 million in incentives. | 1. Building the Strategic Metals Complex (SMC) in Louisiana to serve as a core U.S. rare earth refining/separation hub. 2. Utilizing RapidSX™ technology, which is 10x faster than traditional methods, capable of processing light and some heavy rare earths (Dy/Tb). 3. Production to begin in 2026 at 2,000 tons/year, scaling to 7,500–12,000 tons/year by 2028. | Focuses on separating and refining both light and heavy rare earths. Supported by the DoD as a national security-level project to enhance U.S. processing independence. |

| Ramaco Resources | Rare earths from coal. | $6.1 million in matched funding from the Wyoming state government. | 1. Developing the U.S.’s first pilot plant for extracting rare earths and critical minerals from coal. 2. Aims to meet ~3–5% of U.S. permanent magnet demand and 30% of defense-related needs. 3. Increasing rare earth output from 1,240 to 3,400 tons. 4. Expanding coal production from 2 million to 5 million tons per year. 5. Construction planned to start in H2 2025. | Marks the first new U.S. rare earth mine development in 70 years, with high heavy rare earth content. |

U.S. Legislation Highlights

In addition, the United States has been actively advancing rare earth-related policies at the legislative level. As early as 2020, rare earths were designated by the U.S. government as critical minerals, and subsequent policies have gradually elevated the issue to one of international strategic security.

| Act | Description |

|---|---|

| Energy Act of 2020 (2020) | Designated rare earths as critical minerals; promoted recovery from coal byproducts. |

| REEShore Act (2022) (H.R. 8272) | Expanded REE stockpiles; disclosure of magnet sources; funding for domestic production. |

| Critical Minerals Security Act of 2025 (S. 789) | Required reports on REE supply; U.S. investor exit from hostile nations; allied tech development. |

| Rare Earth Magnet Security Act (2025) | Tax credits for domestic magnets; bans on China-origin REEs; subsidies phased out by 2038. |

| FY2025 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) Critical Minerals Provisions | Strengthened DoD stockpiles and supply chain oversight. |

Summary

U.S. rare earth policy has escalated from industrial support to national security. With only one operating REE mine (Mountain Pass), projects like Brook Mine may become vital to producing heavy REEs domestically.

Even though China still dominates, the U.S., EU, and allies are building alternative supply chains, focusing on security, diversification, and ESG improvements.

Challenges Ahead

The rare earth industry faces multiple challenges. First, mining activities cause severe environmental damage—extracting just one metric ton of rare earth metals can generate around 2,000 metric tons of toxic waste, leading to soil degradation and water pollution, with nearby communities bearing the brunt of the impact. Second, the pace of mining and processing remains far behind growing global demand. While efforts to de-risk and diversify away from China are advancing, replacing China’s supply capacity in the short term remains highly difficult. Any sudden shift in China’s export policies could lead to severe supply chain disruptions and sharp price volatility.

Overall, rare earths are more than just mineral resources—they represent geopolitical leverage, technological strength, and industrial influence. The core aim behind U.S. and EU policy efforts is not only to prevent being “choked” by Chinese supply dominance but also to reassert control over their roles in the global industrial chain. The current trend is moving from regional concentration toward diversified global sourcing, in an effort to reduce risk and enhance national self-sufficiency. However, in the short term, the world remains heavily dependent on China, and the focus remains on gradually reducing risk and strengthening supply chain resilience.